From:

©

©DISTRIBUTED WITH THE

I TA LY DA I LY, T H U R S DAY, M AY 1 8 , 2 0 0 0

©

©CLOSE-UP

By Gabriel Kahn

ITALY DAILY STAFF

At the beginning of 1999, Gherardo Colombo, one of the Milan prosecutors who led the "Clean Hands" investigations into political corruption, and Corrado Stajano, a seasoned journalist, made a pact: For a year, they would write letters back and forth, exchanging views on whatever came to mind or appeared to be the issue of the moment. They remark on the folly of two grown men who live a short distance from one another in Milan, but who, in the age of Internet, resort to Italy’s shaky postal system in order to communicate. What emerged from the experiment is "Ameni inganni: lettere da un paese normale," a slim volume which contains a series of intimate, profound and ultimately sorrowful reflections on a year that was disconcerting for both authors. The title, borrowed from a Giacomo Leopardi poem, roughly translates to "Harmless Deceptions: Letters From a Normal Country." But the title, like many of the observations in the book, is ironic in that the writers see precious little that is harmless in a country that appears stalled in its tracks, unable to take advantage of opportunities and which no longer believes that the collective will of society can bring about positive change. The central reference point for both men is Tangentopoli, the massive political corruption scandal which began in Milan in the early 1990s and for which Mr. Colombo became one of the most important prosecutors. Mr. Stajano was an observer to the spectacle of corruption, bribery and betrayal of public trust that spilled into the open during Tangentopoli. But he was no less taken by the events. Much of the book’s bitterness comes from the disconsolate observations of how the legacy of Tangentopoli is not one of change but of status quo. "It seems that 100 years have passed, not seven, since Feb. 17, 1992, the date of the beginning of Clean Hands," writes Mr. Stajano, remarking on the anniversary of the corruption scandal. "You and the other prosecutors were seen as liberators, applauded, patted on the back, loved… And now? The same people who applauded you and who held you up as saviors are closed in their homes, disillusioned or forgotten." Mr. Colombo responds with

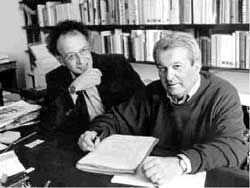

more queries. "I ask myself, in the end, two straightforward questions: Was it worth it to denounce the system of corruption? And, is that same system now r e g e n e r a t i n g itself?" Though he has 26 years experience as a prosecutor and has seen more than a few of his carefully conducted investigations go up in smoke, Mr. Colombo is ultimately not as downcast as Mr. Stajano, 16 years his senior. It is from these two different approaches toward contemporary life that the book derives its dynamism. Mr. Colombo, 53, is a patient jurist who immerses himself in his work and hopes for the best. Because it is a sort of running commentary on a year of headlines, spanning the war in Kosovo, a political assassination in Rome and numerous ongoing legal battles, "Ameni inganni" at times requires an intimate knowledge of recent events. But it also has a disarming frankness, as two public figures open up to one another. In deserted Milan in mid-August, Mr. Stajano relates how he finally went to view the newly restored "Last Supper" fresco, a few feet from his home. He describes how he was left cold by the bright colors of the restored fresco and upon seeing the figure of "Christ in the middle, alone, abandoned, depressed, subdued." Disappointed with the painting, he is more tempted to look out the small window in the church and imagine what Leonardo might have seen as he spent so many hours at work there. "I realized that history touches me more deeply than does art." In another letter, Mr. Colombo tells his friend how one of the most terrifyingthings about being a prosecutor is to be on call for night duty. The ring of the telephone in the pre-dawn hours can only mean a homicideor some otherviolent crime. Even before Clean Hands thrust him and his colleagues into the national spotlight, Mr. Colombo, a Milan native and a graduate of the city’s Catholic University, had worked on some of the shadiest cases in the country’s recent history. He was one of the prosecutors investigating the mysterious murder of Giorgio Ambrosoli, a lawyer who had been appointed to oversee the assets in the Banco Ambrosiano bankruptcy case, Italy’s largest-ever financial scandal. He was also a prosecutor in the P2 Masonic Lodge case. Led by shady financier Licio Gelli, who was also convicted for his role in the Ambrosiano affair, the lodge was supposedly laying the groundwork for a right-wing coup in the 1980s. The names of the P2 members were a who’s who of Italian politics and power, from media magnates to politicians and military officers. He has also published several books on legal matters, and one, "Il vizio della memoria," or "The Bad Habit of Remembering," on his recollections from conducting a series of cases that penetrated to the heart of pubic corruption. What is remarkable about Mr. Colombo is his tempered faith in the face of so many legal and political hurdles that have often impeded his work as a prosecutor. Rooted in a left-wing Catholic tradition, he sees his job in terms of civic duty and rarely admits to being discouraged. Mr. Stajano, 69, on the other hand, has none of the professional distance of Mr. Colombo. Each day’s headlines bring emotions to the fore, often disgust or despair. Though Mr. Stajano describes himself as a journalist, and writes a bi-weekly column in Corriere della Sera, he is really more of a public intellectual, a figure rapidly disappearing in both Europe and America. As a journalist, he has commented on almost a half-century of public events, but has never felt that his role ends with the printed word. In 1994, the Democratic Party of the Left convinced him to run for Senate. But, as he describes in "Promemoria," a book he wrote on his two years as a senator, the experience was disillusioning. Seen from up close, policy issues and principles melt away to leave only crude and facile power games played by adults he describes as immature and almost uncouth. "In Milan, the corruption during the 80s was visible, you could feel it," says Mr. Stajano during a recent interview seated on the sofa in his Milan apartment next to Mr. Colombo. "The arrival of Clean Hands was a sort of liberation. The corruption was so easy to show, everybody knew everything but said nothing." But for Mr. Stajano, the moment of liberation gradually turned sour, not so much for the scarce legal results as for the change in the public’s mood. "I have noticed a fatigue in people. They are tired after all of this caring." "For me it was different," says Mr. Colombo. "If one doesn’t have the necessary distance from these facts, it will condition your work." Mr. Colombo bears the burden of working in a justice system that he himself believes is deeply flawed. "Right now, justice in Italy works really poorly. The trials are so complicated and take so long. A sentence that comes 12 years after the fact doesn’t help anyone." The two authors never question the assumption that Clean Hands was an honest effort to root out corruption in a decrepit political system. For that reason, the book has instantly become a target of those who feel that the corruption scandal had less noble motives. Many, especially survivors from the political parties who were decimated by the Clean Hands investigations, feel that the left-wing prosecutors were carrying out a political vendetta against their enemies, such as current opposition leader Silvio Berlusconi. "Employing the excuse of an epistolary work, the two friends use the occasion to explain to the cultured and the ignorant the Clean Hands’ three-fold secret of Fatima," mocked Valerio Riva in Il Giornale, a conservative Milan daily. But that debate is sideshow to the book’s deeper message: a growing public disinterest in improving society. "I think Italy is heading toward a type of culture that, in its complexity, prefers privilege to solidarity," says Mr. Colombo. For Mr. Stajano, the message is more acute. "I believe that we missed the bus," he says flatly. "I see today’s society as very passive, reluctant to get involved. Obviously, I hope I’m wrong."

‘In Milan, the corruption was so visible you could feel it.’ — Corrado Stajano

© Italy Daily/IHT 2000

The Authors are responsible of their opinions - Gli autori sono responsabili delle loro opinioni - Los autores son responsables de sus opiniones

Disclaimer: All articles are put on line as a service to our readers. We do not get any economical advantage from it. Any copyright violation is involuntarily, we are ready to exclude any article if so requested by the author or copyright owner. Send a message to: copyright@duesicilie.org

![]() Lista/List

Lista/List